Networks

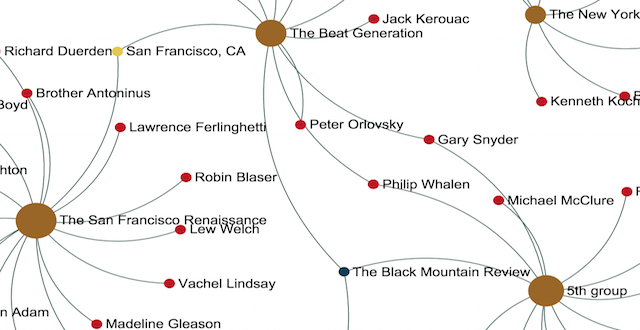

The network graphs here aim to illustrate literary communities. One graph is generated from Donald Allen's remarks about poetic schools in the introduction to The New American Poetry, 1945-1960. Allen associates people, places, and journals with certain schools of poetry: the New York School, the Beats, Black Mountain, and so on. The other network graph visualizes connections among editors, authors, and translators of twelve poetry journals of the era. Networking the New American Poetry seeks to compare the schools Allen describes with the communities detected in the journals' data.

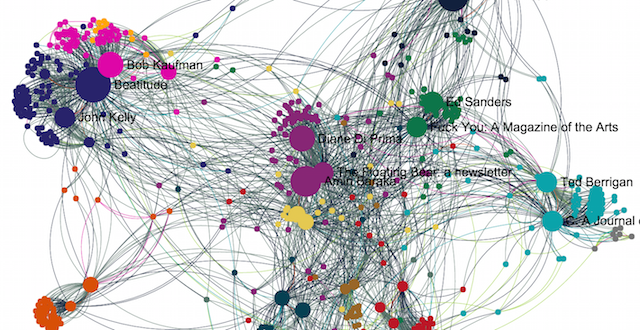

Network graphs are made up of nodes (the points) and edges (the lines that connect the nodes). In the journal contribution graph here, the nodes are journals or people, and the edges represent various relationships. The people are editors, authors, and/or translators with connections to the journals they contributed to, as well as connections to other people. These connections include those between co-editors, co-authors, editors and contributors, and translators and authors.

The size of the nodes are determined by how many connections the node has. If two nodes are connected in multiple ways—for instance, if a person both edited and contributed to a journal—there will be multiple edges between those two nodes. As you zoom into the graph, you will be able to view the node labels. The colors indicate communities, as detected by an algorithm that takes into account the number of connections and the weight of connections. For example, the edge between co-authors will be more heavily weighted than the edge between an author and a journal. Each time you refresh the page, the graph will be laid out anew.

On each people page, you can view an egograph for that person, a subset of the full contributor graph. The egograph displays the person’s individual node, all of the one-degree connections to that node, and connections among those nodes. The egographs include edge labels.1

Observations

The journal contributor graph draws on a much larger and much more complex dataset than that of Allen’s schools. While Allen himself remarked that his divisions “are somewhat arbitrary and cannot be taken as rigid categories,” the journal contributor graph underlines that lack of rigidity by providing a more accurate picture defined by who was contributing to and editing a set of journals. Of course, the goals of an anthologist and the goals of a social network analyst differ widely. Where Allen was trying to selectively curate poets and poems as a tastemaker—an arbiter of the best and brightest—we are trying to reconstruct the significant complexity of Allen’s publishing milieu.

Our graphs represent textual relationships as social relationships because textual relationships originate in social bonds, require social interaction to facilitate production, and expand materially to produce textual communities through shared readership. While some members of our text community were activists and maintained significant public profiles (e.g. LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) and Allen Ginsberg), others were more insular than public, more attuned to literary than public discourse (though of course the two aren’t mutually exclusive). Part of our work here is to give this text community a wider public and, in so doing, to encourage new perspectives on a history as yet half told.

The shape of the communities that we see in the contributor graph suggests a network both less regimented and more capacious than Allen’s anthology indicates. In part, Allen has simply done the work of the anthologist, pruning and aggregating according to taste and other motivations. For us, the “other motivations” are ultimately most interesting and lead us to intriguing questions about the character of interactions and hierarchies within the interlinked textual communities. When we compare Allen’s categories to our graph, we can see that Allen’s poetic schools, which have come to define conversations about mid-century American poetry, were in practice quite permeable, as with the 5th Group and the Beats; and at times his groups are incoherent, as with the San Francisco Renaissance and the New York School.

To put it another way, our graphs show empirically that Allen’s schools have led scholars to overlook significant sites of social and creative activity. For instance, Allen’s schools do not easily accommodate the significant textual communities that arose in the 1960s, after the anthology’s publication. These communities center on magazines and their editors, such as Beatitude (ed. John Kelly and Bob Kaufman), C: A Journal of Poetry (ed. Ted Berrigan), and Intrepid (ed. Allen de Loach). More problematically, we can also observe at least one instance in which a text community that centers on a magazine (Origin) is associated with a school (Black Mountain) whereas the magazine’s editor (Cid Corman), who is also a prolific poet, is not associated with any school—a striking omission. A thoroughgoing look into the history of the period and the archives of these important community members could provide suggestive evidence which would allow scholars to redress the now-conspicuous critical silences that Allen’s anthology has perpetuated.

Conclusion

Much more remains to be said about the ways in which our network helps to rethink the history of literary production in mid-century American poetry and beyond. Among many possibilities, we envision the following three topoi for further investigation:

- Shadow Canons: To what extent do the graphs suggests trajectories for American poetry that scholars have overlooked due to the influence of Allen’s narrative?

- Relative Influence: How might a dataset that includes mainstream anthologies (like the Norton) illuminate the relative influence of Allen’s anthology?

- Network Evolution: How did the network of avant garde poetry publishing evolve over time? Did the geographies shift in significant ways?

Social network analysis provides one way to view historical periods and social groups with new eyes, and we invite scholars to engage with our data and visualizations to develop useful historical and interpretive models.2

This section was peer reviewed by Walter B. Kalaidjian, Department of English, Emory University.

1. To find out more about network graphs, David Easley and Jon Kleinberg's Networks, Crowds, and Markets and Manuel Lima's Visual Complexity offer good starting points. David Easley and Jon Kleinberg, Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning about a Highly Connected World (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); Manuel Lima, Visual Complexity: Mapping Patterns of Information (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2011). ↩

2. For an excellent example of recent work in this vein, see Richard Jean So and Hoyt Long. "Network Analysis and the Sociology of Modernism." boundary 2 40, no. 2 (2013): 147-82. ↩